Pacifism is the belief that violence is unjustifiable under any circumstances, and that all disputes should be settled by peaceful means.

How?

Pacifism is the belief that violence is unjustifiable under any circumstances, and that all disputes should be settled by peaceful means.

How?

The world’s got problems. Poverty, sickness, violence, crime, exploitation, and countless other bad things exist. They are not good. What more, their very existence is a red flag that something must be done. But what?

No matter your politics or philosophy, most of us would agree making the world a better place is a desireable goal. Where we all differ is in deciding what should be done to accomplish that goal.

So let’s break it down.

From the Sermon on the Mount comes the story of the Mote and the Beam. A refresher:

1 Judge not, that ye be not judged.

2 For with what judgment ye judge, ye shall be judged: and with what measure ye mete, it shall be measured to you again.

3 And why beholdest thou the mote that is in thy brother’s eye, but considerest not the beam that is in thine own eye?

4 Or how wilt thou say to thy brother, Let me pull out the mote out of thine eye; and, behold, a beam is in thine own eye?

5 Thou hypocrite, first cast out the beam out of thine own eye; and then shalt thou see clearly to cast out the mote out of thy brother’s eye. — Matthew 7:1-5 KJV

I’m no Biblical scholar. That’s my dad. But what of the mote and the beam? Is it merely a store about being hesitant to judge others? Maybe. Or maybe it’s something more.

If you’ve been reading along lately, you picked up on the fact that last week was my last at Google.

And this week was my first at FullStory.

It’s been a shade under seven years working here at Google in Atlanta; the longest I’ve worked anywhere.

Today is my last day.

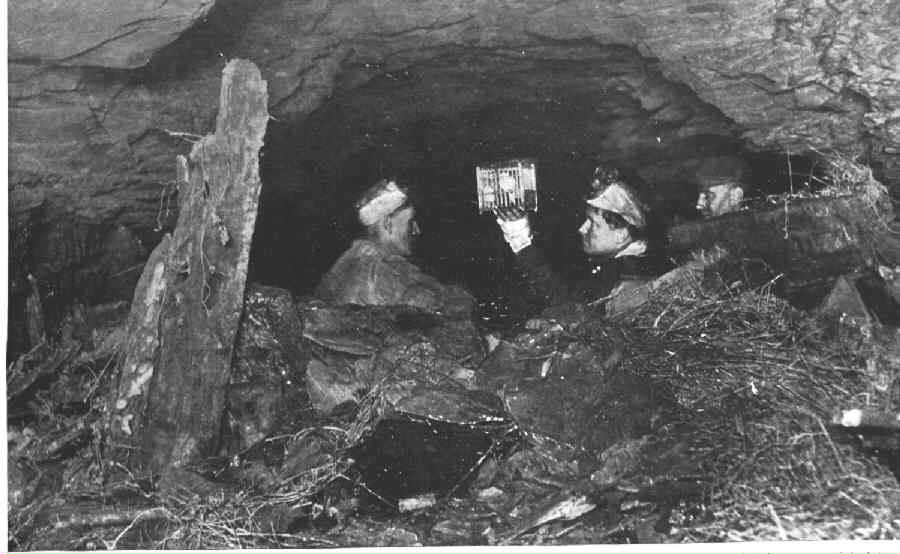

The expression “canary in a coal mine” originates from coal miners using canaries as a kind of early warning system. The miners would take the birds into the mine and periodically check-in on their status. The delicate canaries were more susceptible to gases like carbon monoxide, so if they suddenly stopped moving, miners would be alerted of dangerous air conditions.

Hence, the expression “canary in a coal mine” is an idiomatic way of talking about events that portend negative things to come.

Channeling Clayton Christensen’s Jobs-to-be-done frame, I’ve started thinking about my daily default decisions. What is the job I need done by [fill-in the blank]?

It’s a useful exercise.

I keep thinking about being digitally isolated. What is “digital isolation?” In a nutshell: today we are more connected to anyone/everyone than at any point in history yet (paradoxically) we feel ever more alone. Stranger still, it seems we have chosen this as our preferred mode of existence. There’s even a joke about it: there are nine ways to reach me on my phone without talking to me; pick one of those.

David D. Friedman had a thought-provoking post over over the weekend — Middlemen, Specialization and Birthday Parties. Therein he talks about how specialization and division of labor have allowed for us to cheaply outsource various aspects of our lives that were formerly almost necessarily DIY. Below is an example I can relate to now that I’m living as a parent in my own era of kid’s birthday parties — and note Friedman’s reaction (second paragraph):

It takes mundane, often boring, always repetitive practice. And often a whole lot of it.

We learn by doing and not by thinking.

This strikes me as relevant to mastering any skill, and reminds me of George Leonard’s “Mastery” (a bit of a summary of Mastery can be found by Todd Becker, who prompted me to read Mastery in the first place — it’s a quick, inspiring/challenging book).

Watching that video reminds me of how I “became an artist.” I did a lot of art/cartooning as a kid and people would say to me, “You’re talented.” Being an artist was then, and still is today, looked at as some sort of “gift” bestowed from the heavens (and or my genetics). I’ve never believed this personally though.

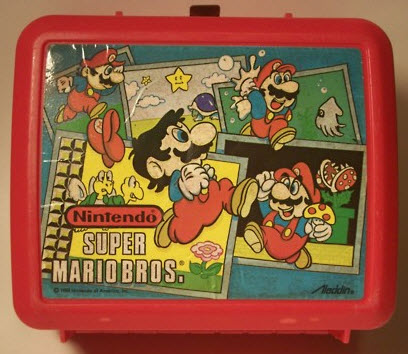

How I became an artist was much simpler: I kept trying to copy the cartoon image of Super Mario over and over and over again, doing it better and better each time. I remember doing it 20-30 times one night for my classmates in maybe 1st grade. What I didn’t realize at the time was that I was inadvertently practicing how to copy something I saw with my eyes and put it down onto paper. Without any prompting or structured learning from parents or teachers, I trained myself as a five or six year old to draw cartoons.

This is the lunchbox that made me an artist:

This is how we learn: practice, perseverance, stumbling, and trial and error.