How Mobile Hijacked Human Nature

We live in abundance, so why does our attention feel so scarce?

Our biology hasn’t caught up to our technology. Today, we live in a time of abundance — abundance of information, content, and connectivity. Yet our time and attention has never felt more scarce — or scattered. How we manage the interplay between these dynamics is critical to our future yet completely unresolved. We are in uncharted territory.

Falling down

The age-old expression “There’s never a dull moment” has never been more true than it is today.

Just look around at the shoppers in line at the store, the drivers at the traffic light, your co-workers at the happy hour, or even — increasingly and frustratingly — your family at the dinner table. What do you see? Downward gazes toward mobile devices. Fingers on glass clearing notifications, swiping feeds, and dealing with something (ostensibly) important.

The smartphone is the escape portal in our pocket that promises transportation to another place. Distraction. Through our phone’s vibrations come whispers of entertainment, work, messages, whatever.

Give me your attention.

So long as you have a signal and a decent charge no amount of time is too small. In the minutes spent waiting, stuck in traffic jams, or walking to meetings; the seconds between bites of food, at periodic pauses in conversation, or lulls in the Netflix shows we stream — we get little chances to escape.

Marginal time made important, unlocked by our smartphones

Where does the time go? Spinning my wheels

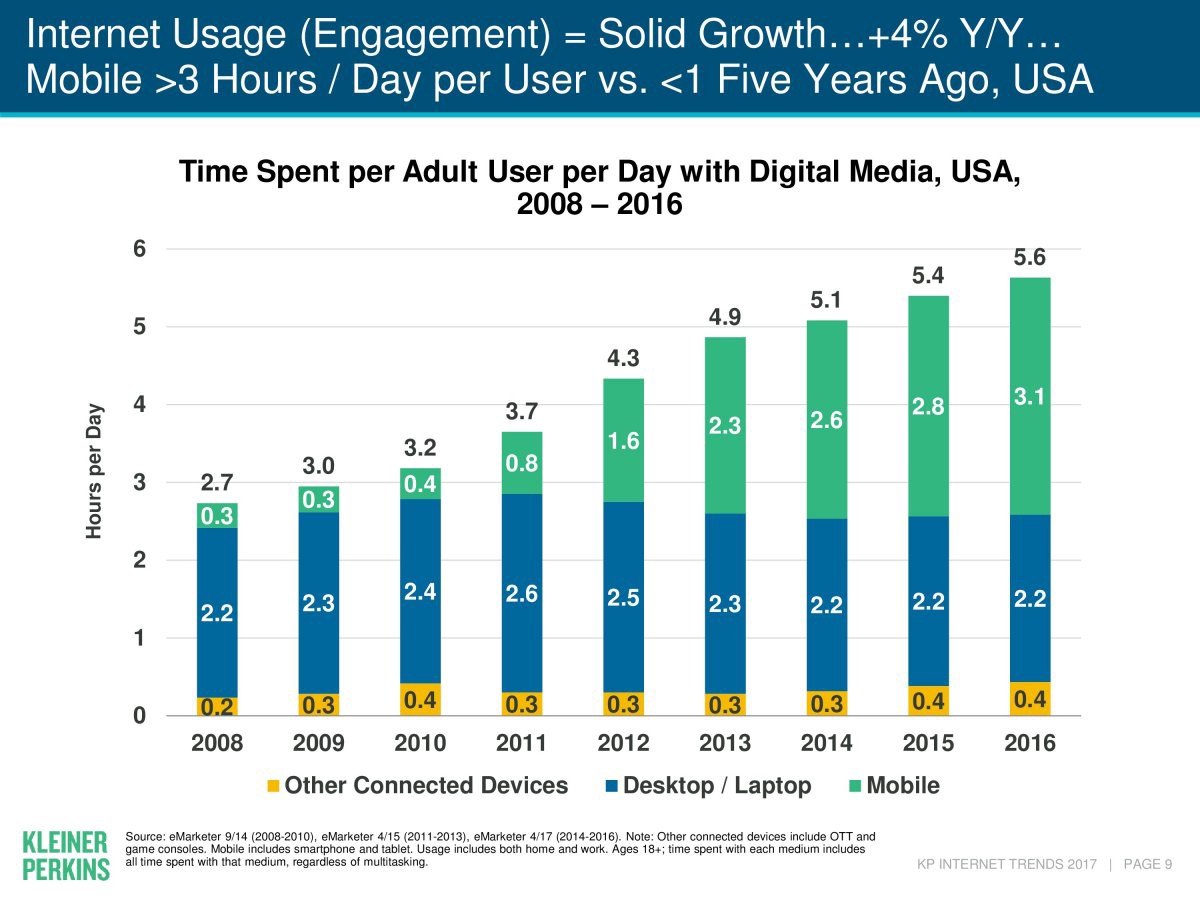

Estimates suggest we are checking our Mobile devices some 110–150 times a day.¹ All those moments add up. Mary Meeker’s 2017 Internet Trends presentation shared that time spent with Mobile has increased from about an hour a day in 2011 to going on 6 hours a day in 2016:

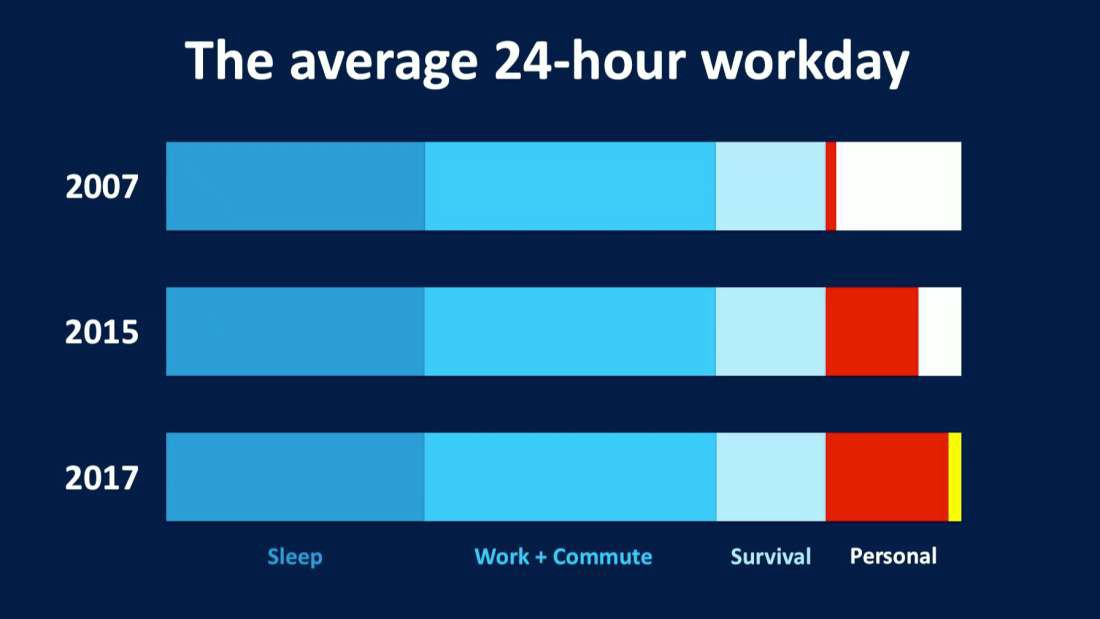

Whether we’ve hit the upper limit in time spent with Mobile or not is yet to be seen (Though there is only so much time in a day). To that end, a recent TED talk given by NYU professor of psychology Adam Alter shared research on the average 24-hour workday, focusing on how time was spent across four categories: Sleep, Work+Commute, Survival, and Personal. You can see the findings below. Note that within “Personal” is a red bar that represents screentime.

Alter’s findings show that from 2007 to 2017 Personal time has been consumed by screentime. It’s hard to grasp the gravity of such a colossal shift in human behavior — one that occurred in a mere ten years, yet self-reflection bears it out. Personal time —our leisure time — feels like it has evaporated. Why?

Standing still — it’s like running on ice

The value of time is highly subjective to the person experiencing its passing. Consider how someone with nowhere to be might not mind a minor delay at a red light. Contrast that same person with someone trying to make it to the airport in time to catch a flight — this person will find waiting at that red light much more painful.

Before the Internet — and especially before smartphones — having meaningful downtime was normal. In your downtime you could turn on the television, read a book, spend time with a friend (or family), or just sit there and do nothing. You could very easily get bored.

But the Internet, as made ubiquitous through our Mobile devices, has connected us to endless opportunities to distract ourselves, do work, do something. While in our connected era, you can still do all of the same things as before, doing something as simple as doing nothing has become downright hard.

Louis C.K. nailed this idea on Conan almost four years ago (0:55s).

You need to build an ability to just be yourself and not be doing something. That’s what the phones are taking away. Is the ability to just sit there like this. That’s being a person, right? — Louis C.K. on Conan

Our constant connectivity made possible by Mobile has made it cheap to always be doing something. By extension it’s raised the price of doing nothing. Doing something on Mobile now costs us only our time and attention. Meanwhile, the price of doing nothing requires willfully ignoring all the possible stuff we could be doing on our Mobile devices.

I only get a little attention when I fall

All of the stuff we can do on Mobile comes down to content creation and consumption. The device in our pocket gives us the opportunity broadcast or to hunt and devour.

The game is plentiful. There has never been more content to consume than there is today. Whether it’s professional content — the kind of stuff you might pay a premium for like a movie, book, streaming video service, music — or amateur content, which is everything that is shared on social media, our lives are inundated with content.

Mobile devices are the ultimate content creation devices — sharing is creation. A short three years ago Mary Meeker estimate that 1.8 billion photos were being uploaded every day. YouTube has over one billion hours of video watched daily. Everyone you know on Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat is their own little micro-celebrity (Twitter, too).

Much of this content amounts to ephemeral noise, but there are enough gems to keep us swiping and searching.

Benedict Evans has written about how our phones are the only device that matters today. It’s the remote control for the world and the Internet is the network. Through Mobile we have access to all the content we could want. Whereas in time’s past distribution channels mattered a great deal (e.g. network TV, cable services, book publishers, music labels, etc.), these proprietary channels matter very little in the age of the Internet.

All of this content clamors for our time and attention. Shouldn’t we be happy to live in a time of such abundance?

Why is it when we look around at our friends and family people seem so distracted, so anxious?

What’s wrong with us?

We aren’t wired for this

If all of our time can be spent doing something over the Internet and there is a never-ending, growing list of things to do — be it content to create or consume, how might we expect humans to behave?

Mobile connectivity has put a price on our marginal time and that price can be understood by turning to the economic concept of “opportunity cost.”

Opportunity cost is the hypothetical future you give up when you make a choice. It’s the imagined missed opportunities. When we think about what we gave up to do something we are filled with discomfort and anxiety — a sense of loss for some potential future that is now gone forever.

Opportunity cost the fear of missing out.

FOMO

Consider this situation. Imagine you’re missing work because of a dentist appointment. As you wait to be called, you see a magazine you could pick up and read. Or you could open your Mobile phone, check your work email, and knock off a couple to-dos. If you choose the magazine (or Facebook, Instagram, etc.), the opportunity cost is the foregone stuff you could have done on your Mobile device.

Here’s another one. You spend 20 minutes scanning Netflix for something to watch. You want to pick something you’ll enjoy, but struggle to sift through the hundreds of options available. You know there has to be something worth watching and that knowledge creates anxiety because, well, you don’t have to watch anything, at all. You better make a good choice — the best choice. Otherwise you’re giving up some other use of your time.

You finally settle on a movie that has decent reviews and you sorta want to watch — only to find that 15 minutes into it, your mind drifts to that possibility engine within arms reach. Hmm … maybe this movie isn’t worth watching, after all.²

Here, the opportunity cost isn’t just the other streaming options you skipped, it’s also the other entertainment options offered up by your Mobile device. Is it a surprise that 70% of streaming, live, or DVR TV watching during Primetime involves other activities³.

Loss aversion and human nature

If you’ve read Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking Fast and Slow you’ll recall his discussion of Loss Aversion and Prospect Theory.

A quick summary.

People are willing to pay a premium to eliminate a small chance of a big loss — the example du jour is settling a frivolous lawsuit. You know the lawsuit is without merit. But even if you have a low probability of losing, the small chance at a big loss nags at you. So you're willing to pay more than would make logical sense to eliminate that small chance.

It's rational to settle your mind even if it may not make statistical sense. After all, you've only got one shot at the suit. Better safe than sorry.

On the other end of the spectrum, you are willing to pay a premium for a small chance at a big gain. That's why you play the lottery. You have almost no chance of winning yet you pay a price for a ticket that's significantly greater than the value of the ticket. Why?

Because “You can’t win if you don’t play.”

Both of these behaviors at the margin help explain why people have anxiety about choices when it comes to how you spend your time —and in particular how you spend your time with content.

What do I mean?

There’s always a good that the content you choose won’t be worth your time. Scroll through any timeline on social for confirmation.

Meanwhile, your Mobile device offers the opportunity for an outsized gain —you have a small chance at making a fortuitous discovery. So what do you do?

You unlock that phone. It calls to you like the glossy slot machine that it is. You play the lottery with your attention, hoping for that outsized gain.

And when you're in the midst of some activity, you struggle to focus on it exclusively — so you hedge your choice by multi-tasking.

Around and around you go, “Damned if you do. Damned if you don’t.”

This is the modern predicament of being connected all the time.

(All this is about spending your time consuming. It doesn't even get into the act of creating content and sharing it on social media, which is like writing your own lottery tickets.)

Reasserting control

I’m tired of telling myself it’s okay to be this tired.

How might we reclaim our time and attention? If anything, it starts with awareness of the problem — we are in uncharted territory when it comes to the interplay of access to information and human biology, which has not evolved to catch up to it’s current environment.

Asserting rationality

Our natural response to turn to the phone to avert potential losses or seek potential gains is irrational, but it’s human. If we can accept the veracity of our nature, we can take steps to thwart it.

Daniel Kahneman talks about cognitive illusions — those times when our brains can’t see the reality of a situation. They are tricked. He makes an analogy to the Müller-Lyer illusion. A.k.a. this:

If you’re familiar with the above illusion, you know that our minds can’t help but see the lines as being different lengths — yet it simply isn’t the case. By being aware of the illusion, we can take assert rationality over our mistaken perceptions.

When we feel the innate drive to pull out our Mobile devices, ready to play the lottery with our attention or avert spending our time in a less-than-optimal way, we can take a deep breath, and realize our brains are up to their instinctive tricks.

We can re-center our focus and put our Mobile phones down.

Meditation

This re-focusing of our attention shares much in common with meditation. Acknowledging distractions that take our focus away from the present — centering on the breath — is critical to meditation.

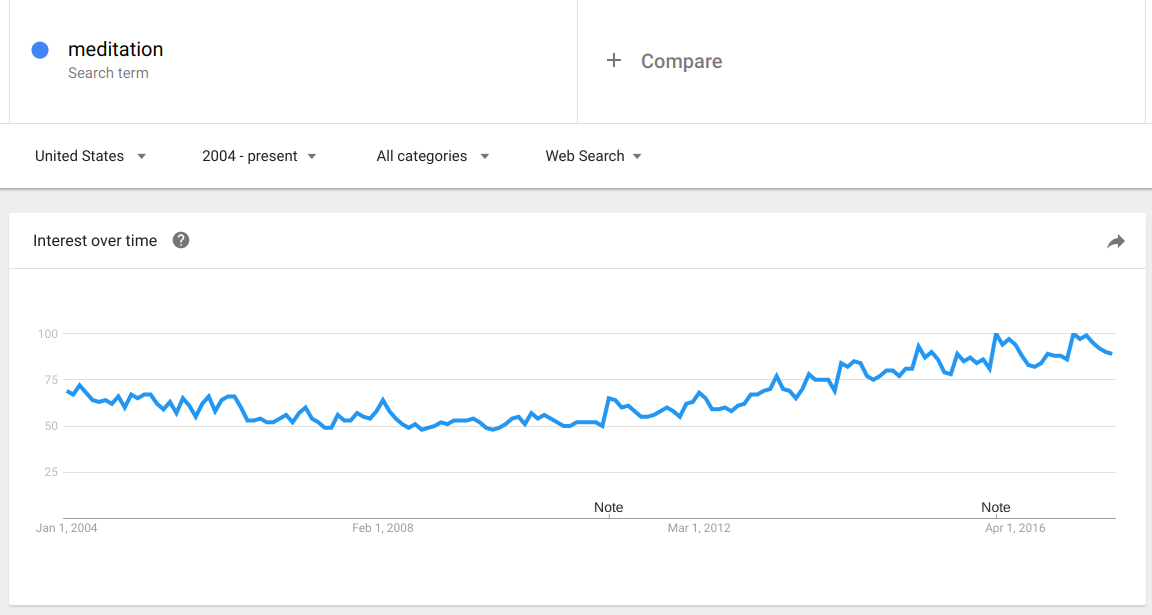

Interest in meditation appears to be on the rise. Take a look at this Google Trends for “meditation:”

Perhaps there’s a chance we finally learn: our quest to optimize every moment of our time is futile. It can’t be done, so why chase the impossible?

The future is unknown

While the future unfolds before us, what’s certain is that there will be no slowing of technology. The demands on our time and attention are only going to become more extreme. What we do about those demands is up to us, but starting from awareness of the problem and taking even small steps to reassert control feel like moves in the right direction.

2024 — See also:

- Another look at the parable of the blind men and the elephant — now everyone's blind, holding their personal elephant in their hand

- Daniel Kahneman's What You See Is All There Is — reshaping reality with stories

¹ Android app Locket pegs the number at 110X/day (October 2013) while the TomiAhonen Almanac from 2013 puts the number at 150X.

² I call this streamer’s remorse.

³ GFK, September 2015

Certain section titles are lyrics from Vertical Horizon’s Falling Down.