Why folks do what they do: Jobs to Be Done

Clayton Christensen, the late author of The Innovator’s Dilemma and former Harvard Business School professor, made the case that to understand what motivates people to act, you first must understand what it is they to need to get done.

You need to know the why behind the what.

Christensen first articulated this outcome-driven innovation in a 2005 paper for the Harvard Business Review titled The Cause and the Cure of Marketing Malpractice, writing:

When people find themselves needing to get a job done, they essentially hire products to do that job for them ...

If a [businessperson] can understand the job, design a product and associated experiences in purchase and use to do that job, and deliver it in a way that reinforces its intended use, then when customers find themselves needing to get that job done they will hire that product.

Christensen’s theory is known as the “Jobs” or “Jobs to Be Done” theory (“JTBD”) because it’s built around a central question: what is the job a person is hiring a product to do? What is the job to be done?

If you can solve the mystery of Jobs to Be Done, you can build the kind of products people love ... like milkshakes for breakfast.

How Do You Satisfy Your Hunger on Your Commute?

Professor Christensen told a wonderful story to illustrate the Jobs to Be Done concept.

It starts with a fast food company’s attempt to make a better milkshake. The fast food company took a classic approach. They identified their target milkshake-slurping demographic and sent researchers to analyze this audience's milkshake preferences. Unfortunately, once the fast food company began making new, evidence-backed and "better" milkshakes based on the research findings, they discovered milkshake sales didn't improve, at all.

What went wrong?

This milkshake story is so good and so well told by Christensen, it's worth the four minutes it takes to hear the late Professor tell the story (YouTube; alternatively, read the transcript of the milkshake story included below).

How do you satisfy your hunger on your commute?

Professor Christensen tells a wonderful story to illustrate JTBD theory. It’s about a fast food company’s attempt to make a better milkshake. Said fast food company took the classic approach. They identified their target milkshake-slurping demographic, surveyed them about their milkshake preferences, implemented their findings, and didn’t improve milkshake sales whatsoever. What happened?

Christensen tells the milkshake story so well that we recommend you give him a listen (4 minutes, YouTube). Alternatively, the story is transcribed below.

Clayton Christensen talks about milkshakes.

We actually hire products to do things for us. And understanding what job we have to do in our lives for which we would hire a product is really the key to cracking this problem of motivating customers to buy what we’re offering.

So I wanted just to tell you a story about a project we did for one of the big fast food restaurants. They were trying to goose up the sales of their milkshakes. They had just studied this problem up the gazoo. They brought in customers who fit the profile of the quintessential milkshake consumer. They’d give them samples and ask, “Could you tell us how we could improve our milkshakes so you’d buy more of them? Do you want it chocolate-ier, cheaper, chunkier, or chewier?”

They’d get very clear feedback and they’d improve the milkshake on those dimensions and it had no impact on sales or profits whatsoever.

So one of our colleagues went in with a different question on his mind. And that was, “I wonder what job arises in people’s lives that cause them to come to this restaurant to hire a milkshake?” We stood in a restaurant for 18 hours one day and just took very careful data. What time did they buy these milkshakes? What were they wearing? Were they alone? Did they buy other food with it? Did they eat it in the restaurant or drive off with it?

It turned out that nearly half of the milkshakes were sold before 8 o’clock in the morning. The people who bought them were always alone. It was the only thing they bought and they all got in the car and drove off with it.

To figure out what job they were trying to hire it to do, we came back the next day and stood outside the restaurant so we could confront these folks as they left milkshake-in-hand. And in language that they could understand we essentially asked, “Excuse me please but I gotta sort this puzzle out. What job were you trying to do for yourself that caused you to come here and hire that milkshake?”

They’d struggle to answer so we then helped them by asking other questions like, “Well, think about the last time you were in the same situation needing to get the same job done but you didn’t come here to hire a milkshake. What did you hire?”

And then as we put all their answers together it became clear that they all had the same job to be done in the morning. That is that they had a long and boring drive to work and they just needed something to do while they drove to keep the commute interesting. One hand had to be on the wheel but someone had given them another hand and there wasn’t anything in it. And they just needed something to do when they drove. They weren’t hungry yet but they knew they would be hungry by 10 o’clock so they also wanted something that would just plunk down there and stay for their morning.

Christensen paraphrasing the commuting milkshake buyer:

“Good question. What do I hire when I do this job? You know, I’ve never framed the question that way before, but last Friday I hired a banana to do the job. Take my word for it. Never hire bananas. They’re gone in three minutes — you’re hungry by 7:30am.

“If you promise not to tell my wife I probably hire donuts twice a week, but they don’t do it well either. They’re gone fast. They crumb all over my clothes. They get my fingers gooey.

“Sometimes I hire bagels but as you know they’re so dry and tasteless. Then I have to steer the car with my knees while I’m putting jam on it and if the phone rings we got a crisis.

“I remember I hired a Snickers bar once but I felt so guilty I’ve never hired Snickers again.

“Let me tell you when I hire this milkshake it is so viscous that it easily takes me 20 minutes to suck it up through that thin little straw. Who cares what the ingredients are — I don’t.

“All I know is I’m full all morning and it fits right here in my cupholder.”

Christensen concludes:

Well it turns out that the milkshake does the job better than any of the competitors, which in the customer’s minds are not Burger King milkshakes but bananas, donuts, bagels, Snickers bars, coffee, and so on.

I hope you can see how if you understand the job, how to improve the product becomes just obvious.

Source: Clayton Christensen, YouTube

“Let me tell you when I hire this milkshake it is so viscous that it easily takes me 20 minutes to suck it up through that thin little straw. Who cares what the ingredients are — I don’t.

“All I know is I’m full all morning and it fits right here in my cupholder.”

Solving Jobs to Be Done With Empathy

How we confuse consumers with consumption.

Christensen’s milkshake story illustrates how asking a direct question—“What would make our milkshakes better?”—is a fast way to arrive at the wrong place.

Should we be surprised? Are milkshake buyers little more than their demographics? Of course not. "Demographic determinism" leads us to a dead end because demographics fail to predict intent.

And in this case, confusing the milkshake consumers with what they hope to do (Satisfy hunger, add excitement to a boring commute, or whatever they hope to accomplish), will result in developing “a one-size-fits-none product,” as Christensen put it. Worse, you can bet this product will do little to nothing for sales.

Meanwhile, a business organized around solving for the actual needs of consumers has a clear reason for being because it’s those needs that drive a customer’s behavior in the first place.

Remember: The consumer is not the same as what they consume.

It’s All About Intent! And Intent Starts With Empathy

Christensen's Jobs to Be Done framework brings to our attention something we all know: intent matters. Everyone has reasons for the choices they make—a need to meet, desire to fulfill, objective in mind, whatever! Shakespeare captured this quintessential insight about human nature some 400 years ago while writing Hamlet: “Though this be madness yet there is method in it.”

If you want to be effective at your job, you need to identify their job. You have to discover what need, desire, or objective they hope to satisfy.

Finding the method behind the madness—that is, the intent of the customer—begins with empathy. Whether you're a product manager, a support professional, a salesperson, marketer, whatever, if you want to be effective at your job, you need to identify their job. You have to discover what need, desire, or objective they hope to satisfy.

Empathy grounds us with a deep understanding of the customer's mind, putting us in that mindset so we can discover intent.

And when it comes to lovable products and customer experiences, you must direct that empathetic understanding toward solving for that intent. And you have to do it better than anyone else.

This is why it's so important to question whether the features we're building or product branches we're developing will do the job better than the nearest alternatives.

Because if the product being developed is built without customer needs in focus, you might find we’ve developed the most amazing product ... only it'll be one that no one wants.

People don’t want to buy a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole!

—Theodore Levitt, Harvard Business Professor

Using Jobs to Be Done to Build More Perfect Products

You can only find the right answer if you ask the right question.

So now you've got a firm grasp on Jobs to Be Done. How do you put it to work? How do you tap into empathy and discover customer intent?

Applying JTBD to understand consumer needs can be as simple as asking, “What did you turn to the last time you needed to do this?”

In Clay Christensen’s milkshake story, this question helped consumers to think back on a previous time they were in the same situation and needed that specific job done. That is, the milkshake buyer needed something to satiate their hunger—or their boredom—on their long commute to work.

It sounds so easy, except we all know how hard it can be to uncover exactly what jobs a customer needs doing.

Which is why we've put together a handful of questions you can ask that can help reveal clues to solve the JTBD mystery.

1. The Switching Question—"You're Fired!"

Is your product so good that your audience would ‘fire’ their current product in order to hire yours?

Reflect on the product you “fired” before hiring the current product. You can tease out why customers choose your product or service by considering what the customer used before they switched to your product. From there, thinking about the “why” can help clarify just what job needs doing.

The “fired” lens in the Jobs to Be Done framework can be used to understand how many once-successful businesses were displaced by competitors that simply did the job better. Examples:

- Netflix doing the job of Blockbuster — “I need something to entertain me ... but I don't want to work too hard to find it.”

- Uber, Lyft replacing taxis — “I need to get from point A to point B easily and painlessly.”

- Google — “I need to know ______ and I'm only willing to work so hard to find the answer.”

- Amazon — “I need to have ______ and I don't want to overpay for a product I'm not confident I'll like.”

- Smartphones — “I need _____” ... Truly smartphones are a JTBD powerhouse, fueling all kinds of businesses over the last 15 years.

Ask this critical question: “Is my product (or service) so good that my intended customer will stop using the product and make the switch?”

“What are people going to stop doing once they start using your product?”

— Jason Fried, Signal vs. Noise

Remember: If you can’t answer the “switching jobs” question clearly, could you reasonably expect a potential customer to?

2. The "WWYSYDH" Question

What does your product or service actually do for someone?

If you’ve seen the movie Office Space you certainly remember when “the Bobs” asked our slacker protagonist a simple question:

“What would you say you do here?”

This simple, straight-to-the-point question deserves some focused attention. If you articulate all the things the product actually does for a customer, you will paint an impression that will help you tease apart what job it is your customer is trying to get done.

Be both specific and general. The details matter more than you might think. The drill makes holes. The milkshake gives you food and it takes awhile to drink. Starbucks gives you energy and it also gives you a place to go. Make a WWYSYDH list.

Contrast your list with the product’s enumerated features. Do the features your product developed solve for the things on your list — the things your customers need doing?

If you’re struggling here, you might also try The 5 Whys. If you’re unfamiliar, this approach is simply asking and answering “Why?” where each answer you provide is further challenged by asking, “Why?”

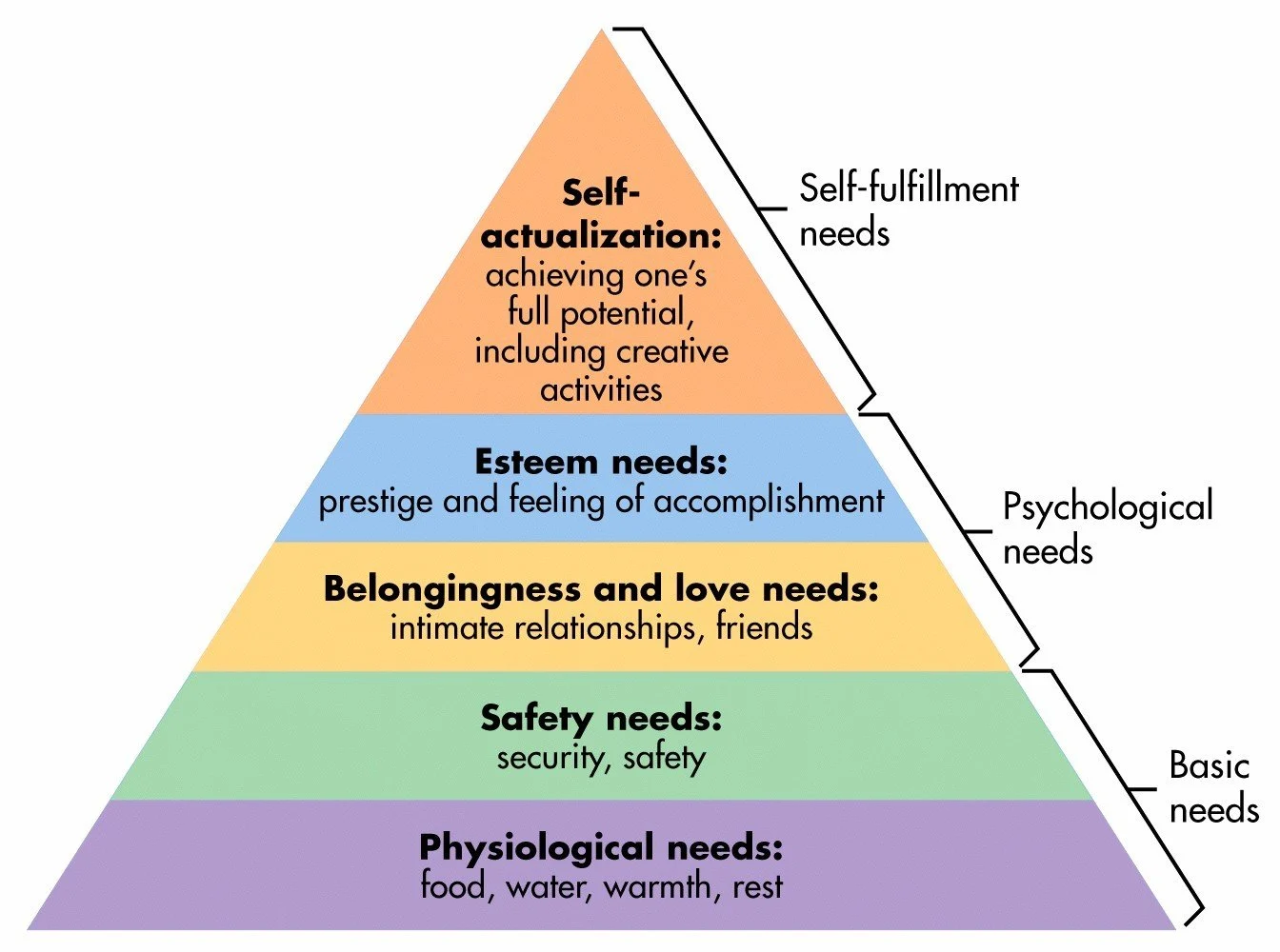

3. The Hierarchy of Needs Question

Remember Maslow's hierarchy of needs? How does your product fill these needs?

Now it's time to go up a level. Think about Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Christensen has written that, “With few exceptions, every job people need or want to do has a social, a functional, and an emotional dimension.”

- What social need does the product solve?

- What emotional need is being solved by the product?

- How will using the product make the customer feel?

While it may seem far-fetched to think of how a given product solves some intangible need of a customer, it makes sense: customers buy products for reasons (see above) that exist under specific circumstances (context). These reasons can be simple or incredibly complex. Meanwhile, because most of us don't question the underlying reasons for why we do the things we do, understanding how our behaviors satisfy our basic needs as human beings can be exceptionally difficult to articulate.

This is why the Jobs to Be Done framework can be extended to understand all sorts of things about others and yourself — from your career choices to your hobbies and relationships. You can ask yourself, “Why am I really doing ______? What is it I really hope to accomplish here?

Apply the Jobs to be Done framework introspectively and you may be surprised what you find.

Build More Perfect Produts With Jobs to Be Done

Now that you're well-versed in the Jobs to Be Done framework, take a second to look at your product roadmap. Does it lead to products that meet the specific outcome expectations of your customers? How could your product better fit their intent?

Evangelize the JTBD theory with your team members. Expect some lively discussion and at least a few "A-ha!" moments.

Apply the Jobs to Be Done lens to every business decision and you'll always have customers ready to hire your product for that job.