"You can just do things" is step one

In Real Life’s Mess I wrote about how organizing a lunch turned into a chaotic reminder of how unpredictable and complicated real-world interactions can be. Organizing that lunch began simply — pick a time and place, send a few emails, provide a clear way to engage, and manage RSVPs.

What I didn't, and couldn't, predict? All the big and little ways people would surprise me. I went in with an Apollonian game plan — neat, linear, direct. But life reacted with Dionysian chaos, throwing surprise after surprise from email miscommunications to extra attendees.

I want certainty, to set the rules and exploit them, but the real world is an exploration in chaos. I can see this as an insurmountable obstacle, and I can stop, give up, and maybe never try again. Or I can see the pushback. I can find harmony in the tension of opposites. If I accept both the plan and the pandemonium, I can do things and come out stronger, ready to tackle the next wall with a grin.

This is all so easy, so obvious when laid out. Except knowing how this dance works is akin to what Mike Tyson famously said, "Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the face."

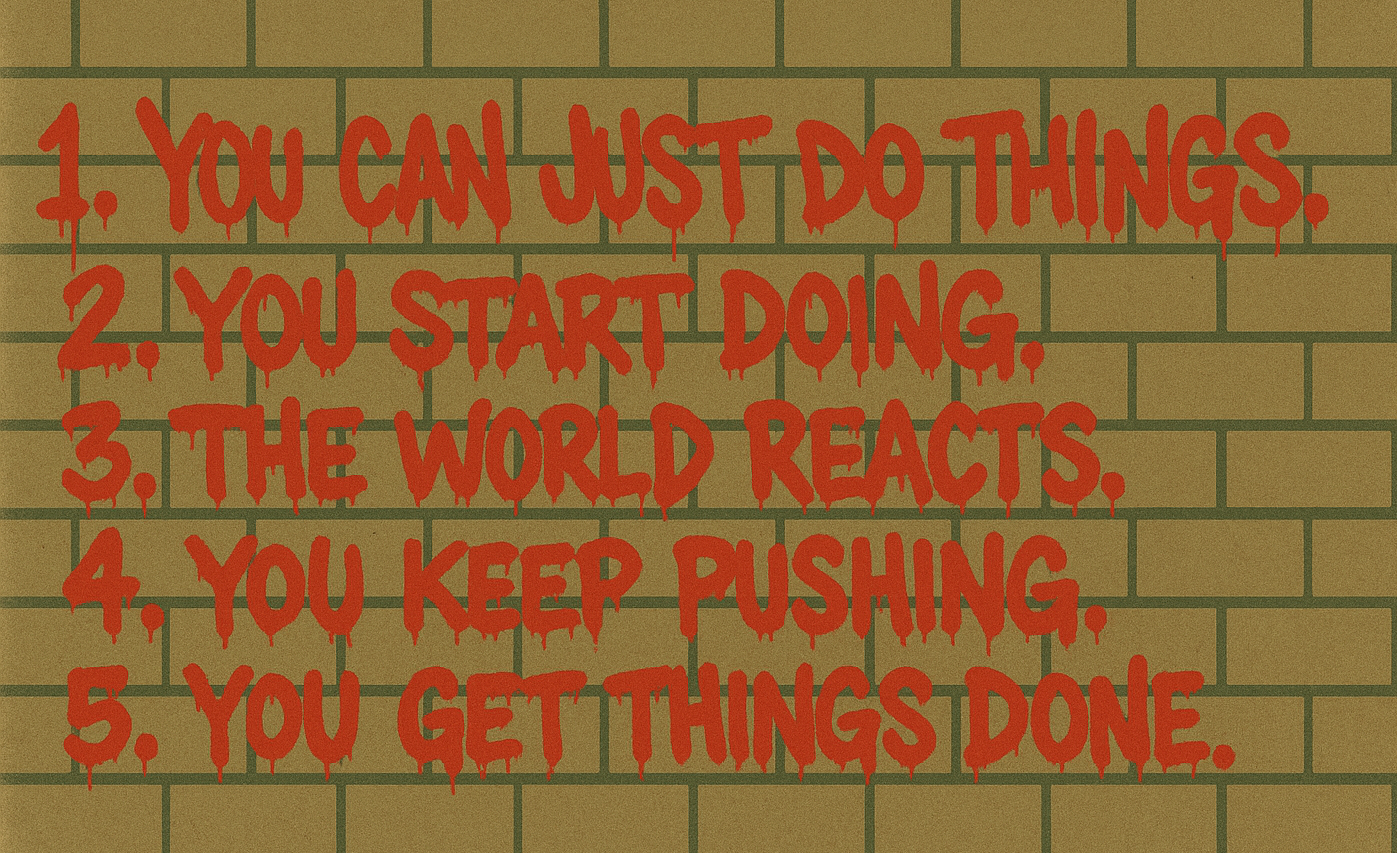

Yes, you can just do things. That's step 1. But what about steps 2, 3, 4, and 5?

Keep pushing until you break through

When you begin to just do things, life pushes back. People get in the way (they're trying to just do things too). You face steps you didn't expect, work you don't know how to do. There's negotiation and compromise.

Doing things means slogging through the inertia of the way things are. Like trudging through two-foot deep mud, the mud sticks to you, holds your legs, weighs you down.

You have to keep pushing. That lunch was a mess of ignored or misread emails, late arrivals, and even waitstaff drama, yet it happened all the same. Everyone showed. The experience was a success. We'll do it again.

The lesson? Yes, you can just do things, but expect to hit walls. You must go full Kool-Aid Man, and smash through the brick with a grin and a shout: "Oh yeah!"

When it's tough, that's a sign that something big is happening. If you push with audacity, you will break through, going from "Can do" to "Can? Did."

The "You Can Just Do Things" process

This "You Can Just Do Things" steps are easy to lay out:

- You can just do things.

- You start doing.

- The world reacts.

- You keep pushing.

- You get things done.

Easy to say, hard to do. Beyond routine tasks, "zero to one," creative work looks more like a sigmoid curve. So much effort with little to nothing to show for it. A Sisyphean struggle, this beginning point is where we most often quit. But if you keep going, things start working, and eventually, they accelerate.

Everything changes.

→ The creative act looks like nothing's happening ... at first

You begin. You push and push and push. Nothing seems to work until, like a sigmoid curve, a phase shift takes place. You go from zero to one, and everything changes.

Why doing things in the real world feels so hard

The creative act has always been this way: Hard. Today it feels harder still. Except the nature of people hasn't changed, so what has?

I think the difference is the pervasiveness of technology. Technology is a lever that makes it possible to turn less labor into more output. Mankind's knack for using technology to solve problems may very well be the real defining characteristic of the species.

Today, technology has encroached into nearly every facet of our lives. With global average screen time per day at nearly seven hours — close to half our waking hours — our default setting is, "There's an app for that." And there usually is. Tech has intermediated everything, from the default way we order goods and services to underpinning our food production and supply to making media creation easier than ever, too, ensuring we are never far from distraction. Consequence? We use more technology — algorithms — to determine what's attention-worthy. And at last we have artificial intelligence, which may upend everything.

Just over the last several weeks, I have had countless back-and-forth conversations across three, sometimes four, AI systems. These interactions are incredible for their depth. I use AI as a thought partner, marveling at how deeply it listens and how thoughtfully it recalls what I’ve said. I use AI as a coach, too, and like a coach it calls me out. I use AI as my personal, genius intern, helping me do more than I ever could have done alone, like generating bespoke illustrations (as for this post) or coding like in the HTML (above) or an annual step calculator I published for BirthdayShoes. It's hard not to love this amazing technology. I also worry about it trains me to believe shortcuts exist for everything, that I don't need anyone, not really.

Whether basic technology like a chat app or Amazon, or advanced technology like AI, what does the adoption of this technology displace? And how has it shifted my beliefs about what's possible? On the one hand, technology has made me more confident than ever about Step 1 — that "I can just do things." However, once I start doing (Step 2) and the real world pushes back (Step 3), it feels harder than ever. Technology has lulled me into believing doing should feel effortless, a series of keystrokes, taps, and step-by-step instructions. My digital reality hides all the hard work under layers of abstractions. The more I use innovative technology to do, the more I believe that this is what progress looks like — problems neatly solved by technology. Somewhere someone is doing things, and we all benefit, standing on the shoulders of their achievement.

Is this progress good?

We deem all of this technology "good," even as we become more and more dependent at every turn. In practice, we are like the kid who's learned to do math but can (finally!) use his calculator. We feel powerful. We are powerful so long as we stay within the confines of what our technology allows.

Soon we forget what it's like to live without our precious levers. The problems that aren't solved easily become problems we can't tackle. We look in earnest for new technological silver bullets and quick-fixes. We distract ourselves silly, resigned to live within the confines of a video-game life, a life that can become plastic, even brittle. We stop imagining life could be any different.

Deep down I worry how this could end. Should the time come when we can't use our technology, we'll be thrown into a chaos we don't understand and without the tools we need to survive. The real world will look disordered, uncertain and therefore unpredictable — incomprehensible. Our technological power taken from us, many would rage, cursing the sky like a child — or adult — whose WiFi has gone down permanently. Many will retreat completely, unwilling to let go of the past and unable to imagine a future without. Will we know what to do?

My prediction may seem dire. I'd agree except we already see evidence it's true. Take, for example, the hikikomori in Japan. These are people who have withdrawn from society entirely, overwhelmed by a real world they’re no longer equipped to face. Life as a hikikomori is possible because of technology — they can bring a digital facsimile of the world to their rooms, supported by a technologically advanced society. Technology makes this possible. But does it make this kind of life inevitable too?

If you squint your eyes you can see how mankind's knack for technology can become pathological. The trend is troubling, but the future is not yet written. All is not lost, not if we recognize the dependencies of technology, remembering there's more to the story in the real world. Not if we have courage enough to return to the Dionysian mess of the real world to "do things." Not if we keep pushing — Step 4! — through the chaos.

There is a balance to strike between resigning ourselves to a comfortable life of certainty and a dangerous life of possibility. My hope is to find that harmony, that beautiful tension of opposites that marries the power of technology with the power of my own agency. My aim is to jump into the fray of reality, engaging in the messiness of life. My prayer is to use technology more than it uses me because my agency is a gift, and I must use it wisely.

For believe me! — the secret for harvesting from existence the greatest fruitfulness and the greatest enjoyment is: to live dangerously!

—Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science

The dangerous practice of life in real world

Hopes and prayers are not enough. I must practice engaging in the real world, facing down the unexpected and unpredictable. I must practice resilience and persistence to be strong. I must live dangerously.

So what am I doing? I start with awareness — that's the thrust of "You can just do things." Though I hear the deadly siren song of technology, I know that I can no more reject technology than reject my humanity. I will use technology to throw myself further, aiming to lever it to the hilt when I can but discard it when it dulls the danger of life. I won't blindly adopt technology without — at least and at first — guessing its costs. And for the technology I adopt, I won't blind myself from knowing what I can about its costs at last.

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor did I wish to practice resignation, unless it was quite necessary. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms, and, if it proved to be mean, why then to get the whole and genuine meanness of it, and publish its meanness to the world; or if it were sublime, to know it by experience, and be able to give a true account of it in my next excursion.

— Henry David Thoreau, Walden

Most importantly, I will make a practice of returning to Thoreau's woods — the real world — to create, to be uncomfortable, to experience the mess of real life.

Practice can look like choosing to do all sorts of things "the hard way." I don't need to reinvent the wheel. Practice can mean organizing gatherings of men in the real world — I know how hard that can be! Or it can be as simple as picking up the phone to call a friend rather than firing off a text. It can involve getting lost instead of using turn-by-turn directions. It must mean exercising my body. Practice must mean challenging my mind — i.e., through focused attention and learning new things. Practice is surely even opting for food that hasn't been deconstructed and reassembled in a factory. Practice is doing things with the living, whether individuals, groups, businesses and organizations, or family.

Practice must unavoidably and always require asserting myself on the real world. If whatever I aim to do scares me, I'm doing something right.

What other ways exist to assert myself on the world without using technology? Also, what ways are there to use the power of technology to attempt things that have never been done before? Artificial Intelligence offers a power unlike any we've seen before. We live in exciting — and frightening — times. And if we are willing to do things, to keep pushing, to overcome the inertia and walls in our way, not only might we do more than we ever dreamed possible, but we may build a momentum that makes us unstoppable.

"Opportunities multiply as you seize them."

— Sun Tzu, The Art of War

I can just do things — so I will! And by doing things, I might find the harmony in the tension of opposites.

Thanks to my friend Isaiah Baker for editorial, from noticing and bringing my attention to the Apollonian/Dionysian to pushing me to make this more personal, to many other things. Finally, Zay has exemplified choosing to live dangerously — he left a high-paying, safe job at one of the most prestigious organizations in the world, Goldman Sachs, to go build a business in south Florida. You must read his story if you haven't. His example teaches me daily that if you want to fully immerse yourself into the Dionysian messiness of the real world, start a business.